Synopsis

Original

Translation

Recordings

Really Zooming in on Gift-Giving

The Value of a Skilled Smith

Closing

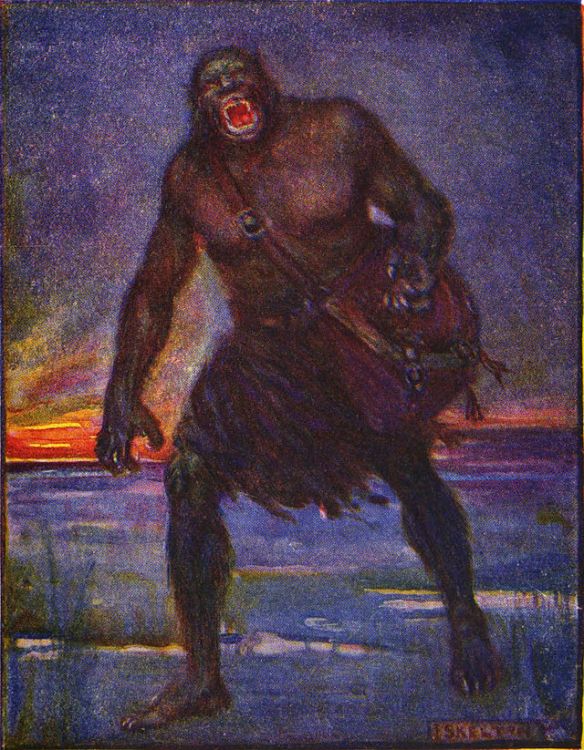

The grip and pommel of the Gilling Sword, found in a stream in Yorkshire in 1976. Did the giant’s sword that Beowulf found have a similar hilt? Copyright York Museums Trust http://bit.ly/2gh8HXJ. Image from http://bit.ly/2gpntKw.

Back To Top

Synopsis

The poet describes Beowulf’s gifting the hilt of his found giant sword to Hrothgar, and reiterates the Grendels’ defeat.

Back To Top

Original

Ða wæs gylden hilt gamelum rince,

harum hildfruman, on hand gyfen,

enta ærgeweorc; hit on æht gehwearf

æfter deofla hryre Denigea frean,

wundorsmiþa geweorc, ond þa þas worold ofgeaf

gromheort guma, godes ondsaca,

morðres scyldig, ond his modor eac,

on geweald gehwearf woroldcyninga

ðæm selestan be sæm tweonum

ðara þe on Scedenigge sceattas dælde.

(Beowulf ll.1677-1686)

Back To Top

Translation

“Then was the golden hilt given into the hand

of the old battle-chief, an ancient work of giants

for the aged ruler. It became the possession

of the Danish prince after those devils perished,

the craft of a skilled smith; when the hostile-hearted,

the enemies of god, gave up this world,

guilty of murder, he and and his mother as well.

Thus the hilt came into the power of the worldly king

judged to be the best between the two seas,

a treasure freely given to the Danes.”

(Beowulf ll.1677-1686)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Really Zooming in on Gift-Giving

This passage is weird. I mean, why spend so many words on the simple act of Beowulf giving Hrothgar the hilt of the sword that Grendel’s mother’s blood melted? It’s a strange thing to dwell on, and I can’t help but feel like it might have been a late addition.

Or, maybe like Homer’s asides and flashbacks in the Odyssey, this is meant to be a moment outside of and within time simultaneously. I’m thinking particularly of when Odysseus gets back to Ithaca and the nurse who raised him recognizes him because of a scar on his thigh. Homer uses her seeing the scar as an in to explain its origin in a brief aside.

But, maybe because the Beowulf poet’s story is about people who see themselves as a little rougher around the edges than the ancient Greeks saw themselves, scars don’t matter. And so this aside comes from an act of giving. After all, the act of giving in early British cultures was huge. It was through giving that wealth was distributed and people were meant to feel that things were given fairly. So, perhaps, along with defeating the monsters terrorizing Heorot, this hilt is meant as a tangible gift that Beowulf gives in return for all that Hrothgar gives him.

Which is kind of suiting since, although the poet calls Hrothgar a “battle-chief” (“hild-fruma” (l.1678)), he is also called “old” twice in close succession (“gamelum” on line 1677, and “harum” on line 1678). These mentions make it clear that Hrothgar’s fighting days are over.

With that in mind, how better to mark the ending of the need for such a strong leader to fight than with the hilt of an ancient sword? It too can no longer be used to fight effectively, but it also has much to say and old stories to share — as we’ll see in next week’s post.

What do you think the poet meant by going on for so long about Beowulf giving Hrothgar the hilt of the sword he found in the Grendels’ hall?

Back To Top

The Value of a Skilled Smith

It is the wish of every leader, every “battle-chief”1,

who finds themselves standing tall as an “earthly king”2,

that they have a “skilled smith”3 in their midst,

one familiar with the methods and means of “ancient works”4.

If such a smith is truly skilled and willing, then that ruler

May wield power and style against the “hostile minded”5.

1hild-fruma: battle-chief, prince, emperor. hild (war, combat) + frum (prince, king, chief, ruler)

2woruld-cyning: earthly king. woruld (world, age) + cyning (king, ruler, God, Christ, Satan)

3wundor-smiþ: skilled smith. wundor (wonder, miracle, marvel, portent, horror, wondrous thing, monster) + smiþ (handicraftsman, smith, blacksmith, armourer, carpenter)

4aer-geweorc: work of olden times. aer (before that, soon, formerly, beforehand, previously, already, lately, till) + geweorc (work, workmanship, labour, construction, structure, edifice, military work, fortification)

5gram-heort: hostile-minded. gram (angry, cruel, fierce, oppressive, hostile, enemy) + heorte (heart, breast, soul, spirit, will, desire, courage, mind, intellect, affections)

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, Hrothgar handles the hilt and reveals its meaning.

You can find the next part of Beowulf here.