Introduction

Recap & Synopsis

The Original Old English

My Translation

A Quick Interpretation

Closing

A barrow known as Wayland’s Smithy. Perhaps the Last Survivor stowed his people’s treasures in a similar place. Image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wayland_Smithy_Long_barrow.jpg

Back To Top

Recap & Synopsis

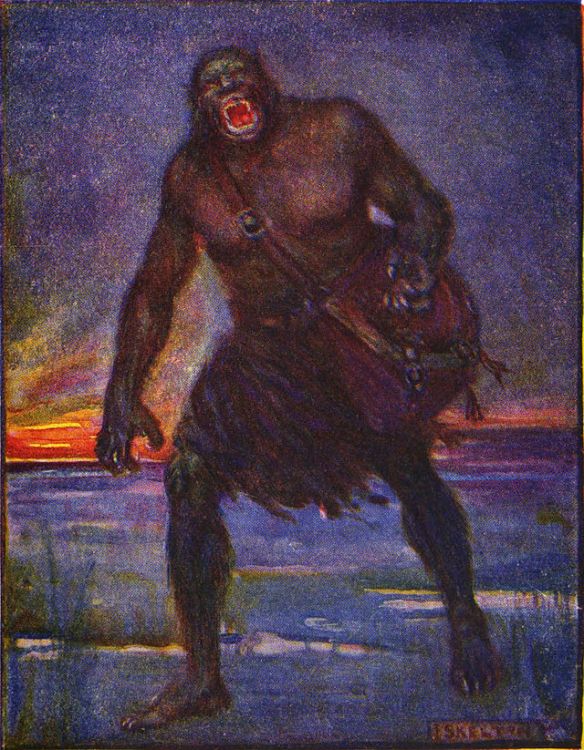

Last week we heard about how the dragon was terrorizing the Geats. Why? Because a cup was stolen from its hoard of treasures.

This week, we hear the Lay of the Last Survivor. These are the final words of the last living member of the tribe who lived where the Geats now live and hid their treasures there.

Back To Top

The Original Old English

“Beorh eallgearo

wunode on wonge wæteryðum neah,

niwe be næsse, nearocræftum fæst.

þær on innan bær eorlgestreona

hringa hyrde hordwyrðne dæl,

fættan goldes, fea worda cwæð:

‘Heald þu nu, hruse, nu hæleð ne moston,

eorla æhte! Hwæt, hyt ær on ðe

gode begeaton. Guðdeað fornam,

feorhbealo frecne, fyra gehwylcne

leoda minra, þara ðe þis lif ofgeaf,

gesawon seledream. Ic nah hwa sweord wege

oððe feormie fæted wæge,

dryncfæt deore; duguð ellor sceoc.

Sceal se hearda helm hyrsted golde

fætum befeallen; feormynd swefað,

þa ðe beadogriman bywan sceoldon,

ge swylce seo herepad, sio æt hilde gebad

ofer borda gebræc bite irena,

brosnað æfter beorne. Ne mæg byrnan hring

æfter wigfruman wide feran,

hæleðum be healfe. Næs hearpan wyn,

gomen gleobeames, ne god hafoc

geond sæl swingeð, ne se swifta mearh

burhstede beateð. Bealocwealm hafað

fela feorhcynna forð onsended!’

Swa giomormod giohðo mænde

an æfter eallum, unbliðe hwearf

dæges ond nihtes, oððæt deaðes wylm

hran æt heortan.”

(Beowulf ll.2241b-2270a)

Back To Top

My Translation

“The barrow stood ready

in open ground near the sea-waves.

It was newly made at the headland, made secure with the art of secrecy.

Within there the keeper of the ancient earls’ ringed treasure

carried that share of worthy treasures,

the hoard of plated gold; these few words he spoke:

‘Hold you now, oh earth, that which men and women cannot,

enjoy these warriors’ possessions! Indeed it was

obtained from you at the first, dug up

by worthy men. But death in battle bore those delvers away.

Now that terrible mortal harm has carried off each and every one of my people.

They have left this life where they knew and looked back longingly

at the joy had in the hall. I now have no-one to bear the sword

or bring the plated cup, that precious drinking vessel.

That group of tried warriors has since passed elsewhere.

Their hard helmets with gold adornment shall be bereft of their gold plate;

the burnishers sleep the sleep of death, those who should polish the battle mask.

So too the battle garbs, that had endured in battle

through the clash of shields and cut of swords,

they now decay upon the warriors’ husks; nor may the mailcoats of rings

go with the war-leader on his long journey,

they may not be kept at their bloodied sides. No harp joy,

no delight of musical instruments, nor any good hawk

flies through the hall, nor any swift mare

stops in the flowered courtyard. Destructive death

has sent forth all others of my race, as it has with countless others.’

Just so, sad at heart, this one followed his kin.

He expressed his sorrow, he moved about joyless,

for unlit days and for fevered nights, until death’s surging

reached his heart.”

(Beowulf ll.2241b-2270a)

Back To Top

A Quick Interpretation

This is one of the big deal parts of the poem. Much like Hrothgar’s speeches to Beowulf about being a good king, it delivers the other of the poem’s major messages: riches are useless without others to enjoy them with.

I mean, this Twilight Zone-esque last survivor has no hope of enjoying or using all this treasure. He can’t strum the harp while polishing helmets and swinging a sword as he waits for his hawk to come to rest on his hand. Not because he doesn’t have those things, but because he has no one to do those things in tandem with.

Though it’s kind of strange. I really wonder about this last survivor and the sort of society that he comes from.

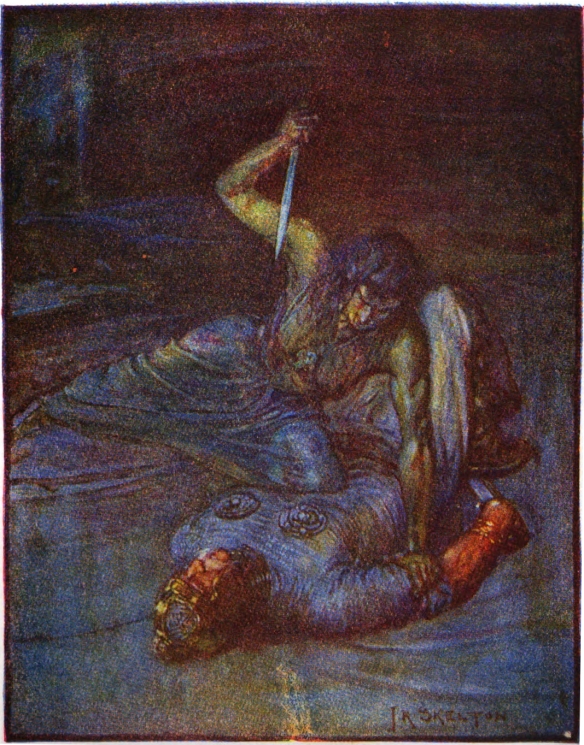

How did they amass all these treasures? It doesn’t sound like they were won necessarily. Instead it sounds more like his people dug up the raw materials, and then created the helmets and cups and mail and swords themselves.

So is this some sort of advanced ancient society situation?

Or, since the Geats, this sea-faring people, are anchored in their homeland, is this situation the fantasy of finding a land completely bereft of settlers but still home to their treasures?

Is this a metaphor for the Anglo-Saxons coming to Britain and then just kind of sweeping the Britons under the rug?

And why is this one guy the lone survivor? Did some sort of disease sweep through his group and he was the only one with immunities against it?

Was he the only one who was out hunting when a wild band of raiders slaughtered everyone else?

There aren’t really any answers to these questions unfortunately.

But that’s just what seems to happen when you try to logic through Beowulf.

What’s more important to the poet or their audience is that the theme of this passage fits with the rest of the poem. It has a melancholic tone and really emphasizes the idea that possessions are both incredible and incredibly useless without others to enjoy them with.

Unless, of course, you’re a dragon. But we’ll see more of that in coming weeks.

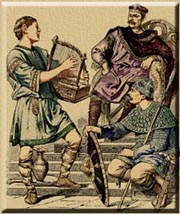

Tabletop games were big throughout the middle ages, and the Last Survivor reminds me of The Lost Tribes from the game Small World. What’s your favourite tabletop game?

Mine would have to be Time Stories. (I still haven’t played the Beowulf game, after all 😉 )

Share your favourite board game in the comments!

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, we learn what happened to the thief who stole the cup and kicked all this off.

You can find the next part of Beowulf here.