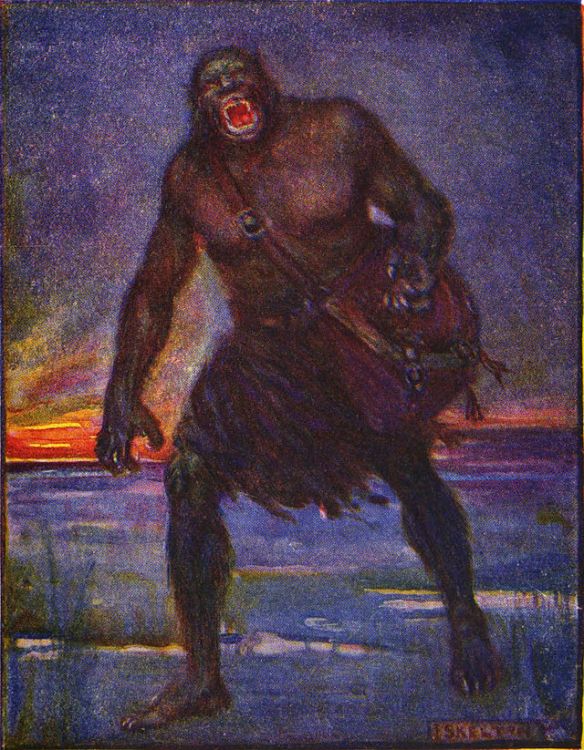

An illustration of Beowulf fighting the dragon that appears at the end of the epic poem. Illustration in the children’s book Stories of Beowulf (H. E. Marshall). Published in New York in 1908 by E. P. Dutton & Company. Image found at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beowulf_and_the_dragon.jpg.

XXXIV

Though the fall of the prince made Beowulf mindful,

worried for retribution as days dragged on, he turned to Eadgils,

a man destitute of friends. That people,

those of the sons of Ohthere, Eadgils helped

with warriors and weapons. The feud was settled after a chill cold,

a cruel campaign, when he bound old king Onela in death.

Thus Beowulf survived strife from all quarters,

savage battles and slaughter, that son of Ecgtheow,

brave doer of good deeds, until that day.

The day on which Beowulf was fated to war with the dragon.

Then it was that the scaled one, maddened with rage, knew the twelve;

the dragon recognized the Geatish lord.

Beowulf soon discovered the reason why that fiend arose,

brought adversity to his people. Into his lap fell the famed cup,

wrought of gold and set with stones, fresh from the finder’s hand.

That man made their party’s number thirteen,

he who had created this dire fate,

a captive of sorrowful heart. The thief agreed to serve

as guide for Beowulf and his men through the dragon’s place.

Against his will he went to the earthen hall which he alone knew.

The barrow beneath the earth, out by the sea billows,

where wave strove with wave, within, it was full of treasures,

both wrought and wound. But the horrible warden,

that eager ancient warrior, was bent on guarding his gold-treasures,

both as old as stones beneath the earth. It would not be easy

for Beowulf to bargain with that dragon for his people’s lives!

Sat then the veteran king upon the clifftop.

He wished his hearth companions luck,

the gold friend of the Geats. His mind was sorrowful,

he was restless and ready for death, fate had come immeasurably near,

he knew that soon he would fully face old age,

that it would soon seek his soul’s hoard, tear his life

from his body. Not long from then would that lord’s

flesh unravel from his spirit.

Beowulf spoke, the son of Ecgtheow:

“Countless were the skirmishes that I survived in youth,

numerous times of war. I can recall them all.

I was seven winters old when I fostered with our treasure lord,

the lord and friend of our people, at my father’s command.

The good king Hrethel kept me and cherished me,

he gave me treasure goods and solemn office, mindful of our kinship.

Indeed, while living in the stronghold as a boy I was not counted

less worthy than his own sons,

Herebeald and Hæthcyn, and my dear Hygelac.

The eldest son, by a deed of his brother,

was impiously spread on his deathbed,

Hæthcyn had hoisted his horn-tipped bow toward the boy,

and loosed the arrow that shattered his life.

He had aimed for a misted mark and shot his own kin,

bloodied his fatal dart with the life of his own brother.

That was a strife beyond recompense, transgression against sin itself,

a steeping of the heart in sadness. What else should be done but

to leave the offence the eldest carried out unavenged?”

“Then was the whole household like a sorrowful old man

who must live on, though his young son hangs on the gallows.

Such a man then makes a dirge, distressed singing,

while his son hangs at the mocking mercy of ravens,

birds gloating over their feast, and he can do nothing

to help his son, no water from his well of experience and age

will allow him to haul the boy down and lavish new life onto his lank body.

Reluctantly he is reminded each morning of

his son’s death. He does not care to wait

for another heir in his hall, since the

first has been found fettered, devoured, by death’s dire decree.

He looks on with tear-filled soul into his lost son’s chambers,

all hall joy now desolation, the resting place of winds,

a place bereft of all joy. The riders sleep.

The fighters lay in darkness. No harp sounds are there.

There are no men in the yard. Nothing is as it once was.”

XXXV

“Then Hrethel was in bed, chanting a dirge,

alone even with himself. To him it all seemed too huge,

the fields’ roll, the halls’ stretch. Thus the Geat’s protector,

his heart suffused with sorrow for Herebeald,

set out for that far country. He never knew how he might

wreak his feud on the slayer;

in no way could he hate that warrior

for his dolorous deed, though he was not loved.

Then Hrethel, amidst that sorrow, that which sorely concerned him,

gave up on the enjoyment of life, chose God’s light.

He left all he had on earth to his sons, as any prosperous man does,

lands and towns, when he left off this life.”

“After that, there was war and enmity between Swedes and Geats,

over the wide waters could be heard their cries of sorrow,

the noise of wall-hard warfare, after Hrethel perished.

From across that water came Ongeontheow’s sons,

warlike, they would not free those

they held in lamentation, they would not relent.

Near the hill of Hreosnburgh they often launched voracious

murderous attacks. My own close-kin avenged this,

feud and war-fire, as it was known,

though one of them bought it with his life,

at a hard price; Hæthcyn, Geatish lord,

was taken in the war’s assailing.

Then in the morning I heard that his kin

avenged him by the blade, laid its edge to end the slayer’s life,

where Eofor’s attack fell upon Ongeontheow.

His war-helm was split, the Swedish warlord

fell, mortally wounded, for Eofor’s hand held memory

enough of the feuding, Ongeontheow could not hold off the fatal blow.”

“The treasures that Hygelac granted me

were payment for my role in that war, all of which fortune allowed me,

I won it for him by flashing sword. For that he gave me land,

a place to be from, the joy of home. Thus, for Hygelac there was

no need, no reason to be required to seek someone from the Gifthas,

or the Spear-Danes, or the Swedes for worse war-makers, my worth was well-known.

Always would I go on foot before him,

first in the line, and so shall I do ‘til age takes me,

so shall I conduct war, as long as this sword survives,

that which has and will endure.

For this is the sword I held when I, for nobility’s sake,

became the hand-slayer of Day Raven the Frank.

No treasure at all did that warrior

bring back to the Frisian king.

No breastplate could he have carried,

for in the field he fell as standard bearer,

princely in courage. He was not slain by the sword,

but instead a hostile grip halted the surge of his heart,

broke his bone-house. Now shall the sword’s edge,

hand and hard blade, be heaved against the sentinel of the hoard.”

Beowulf spoke further after a pause, made a formal boast

for the final time.

“In youth I

risked much in combat, yet I will once more.

Though I am now an old king of the people, I shall pursue this feud,

gain glory, if only the fiend to men

will come out from his earth-hall to face me!”

Addressed he then each warrior,

speaking true to each helm-wearer, for the last time,

every gathered dear companion:

‘I would not bear a sword,

bring the weapon to the wyrm, if I knew how

I might otherwise grapple gallantly against

that foe, as I once with Grendel did.

But there will be hot war-fires I expect,

stinking breath and venom. Thus I have on

both shield and byrnie. And I will not give

a foot’s length when I meet the barrow’s guard, but between us two

what is to happen later on the sea-wall, that is as fate.

The Measurer of Men is indeed to decide. I am firm of heart,

so that I may desist from boasting over this war-flyer.

Wait you all on the barrow, my armed men,

warriors ready in war-gear, while we see which

of we two can endure the wounds

after our deadly onslaught. This is not your fight,

nor any other man’s, but mine alone.

I must share my might with the foe,

indeed, I must share my courage. By that courage shall

I win the gold, or, in this battle, gain the peril of a violent death,

if the latter, may your lord be swept away!”

Arose then behind the shield that renowned warrior,

hard under helm, bore his battle shirt

beneath the stony cliffs. He trusted in the slaughter

one man alone was capable of. That was no cowardly course of action!

Then by the wall the one who had survived

with good manly virtue a great many battles,

the crash of colliding shields and spears, survived when bands on foot clashed,

saw standing a stone arch, a stream came out from there,

burst from the barrow, and soon exploded into

a raging flume of hot deadly fire. Beowulf could not be near

the hoard for any length of time without being burned up,

he could not survive in the depths of the dragon’s flame.

Standing there, watching, he allowed it from his breast, released his rage,

the lord of the Weder-Geats sent the word out,

fierce-hearted he shouted, his voice came in

clean as the clang of battle as it reverberated under the grey stone.

Hatred was aroused, the hoard guardian recognized

man speech. Then there was no more time

to ask for friendship. First came the breath

of the fierce assailant from out of the stones,

a hot vapour of battle. The earth resounded with the creature’s calling.

The warrior below the barrow, the lord of the Geats,

swung the rim of his shield against the dreadful stranger,

then the coiled creature’s heart ignited,

it became eager to seek battle. The good war-king

had already drawn his his sword, the ancient heirloom,

sharp of edges, each was in horror at the intent

to harm and rain destruction evident in the other’s eyes.

Yet, Beowulf stood firmly against the towering shield,

the lord of a dear people, when the serpent coiled himself

quickly together. Beowulf waited in arms.

Then the serpent went gliding along, still coiled and burning,

hastening toward his fate. The shield protected

Beowulf’s being and body for a lesser time

than that renowned prince required for his purpose,

that was the first time that day

that he learned he would have to prevail, though fate had not decreed

triumph for him. The lord of the Geats

swung up his hand, the one terrible in its varied colours was struck by

the mighty heirloom, yet its long-tested edge failed,

it gleamed dry, stopped by the beast’s bones, bit less strongly

just when the king of a people had need of it,

when it could have cut him free from his afflictions.

Then was the barrow

guard, after that battle stroke, thrust into a fierceness of spirit –

it threw its deadly fire, wildly leapt

those battle lights. Of glorious victory the

gold-giving friend of the Geats could not boast then,

the war sword failed him while unsheathed in battle, as it should

not have, it became known as iron formerly excellent. That was no easy

journey, when the renowned kin of Ecgtheow

knew he must give up that ground,

that he should, against his wish, inhabit a dwelling place

elsewhere, but so shall each man

leave off his loaned days. Then not long was it

before the fierce warriors met each other again.

The hoard guard himself took heart — his breast began to heave

from strain — he lunged forth once again. Harsh straits were suffered,

the fires enveloped Beowulf, he who once had ruled the people.

Not any of the band of comrades were with him then.

Those sons of nobility stood around stupefied. Merely draped in martial virtues,

they fled into the woods at the sight below,

eager to save their own lives. In only one mind among them

surged sorrow. After all, kinship may never

for anything be turned away from if a man thinks rightly.

—

Want more Beowulf? Continue the poem here!