Synopsis

Translation

Recordings

Why Hrunting Had to Fail, and Grendel’s Mother’s True Threat

How to Face a Water Witch

Closing

Back To Top

Synopsis

The sword Unferth leant to Beowulf fails him, just as Grendel’s mother advances on our shocked hero.

Back To Top

Translation

Then clearly he saw that accursed woman of the deep,

the strong sea-woman; a mighty blow he gave

with his battle blade, he held nothing back in his handstroke,

so that the ring patterned sword sang out upon her head

its greedy battle dirge. Yet there that surface dweller discovered

that the flashing sword would not bite,

that it would not harm his target’s life: the sword failed

that prince in his time of need. Before it had endured many

hand to hand combats, had often shorn away helmets,

sliced through the fated ones’ war garments; that was the first time

that dear treasure failed to show forth its true glory.

(Beowulf ll.1518-1528)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Why Hrunting Had to Fail, and Grendel’s Mother’s True Threat

A few entries back, I mentioned that Hrunting was the first named sword in the poem. Well, for all of the power and mystery and strength that’s implied for a sword when it’s given a name, Hrunting’s glory is short lived.

The sword proves useless in this fight, just as Beowulf needs it most. After all, if the sword worked as it should, then his attack should have ended the battle before it began. But, for a reason that the poet never gives (except through the audience’s assumption that Grendel’s mother shares her son’s immunity to weapons), Hrunting has no effect. It’s as if Beowulf just found an electric Pokemon to help him take out a gym leader’s ground type Pokemon, and he never realized that ground-types are immune to electric types. Unfortunately, for all of their board games and riddles, I don’t think the Anglo-Saxons had charts drawn up showing the strengths and weaknesses of various monsters to various heirloom swords.

Actually, I find the failure of Hrunting funny.

It’s supposed to be this 100% never fail, surefire thing, but then, in Beowulf’s hands, it fails.

Had it succeeded in killing Grendel’s mother in a single blow, where would the glory for a hero like Beowulf be? She’d be just like any other foe he’s faced. And that just wouldn’t do; the reputation of the sword needed to take the hit for Beowulf’s sake.

In fact, if Beowulf killed Grendel’s Mother in one strike, then she would’ve been weaker than Grendel. I mean, Beowulf had to wrestle Grendel for some time before he tore off the monster’s arm. And that’s not how this can work.

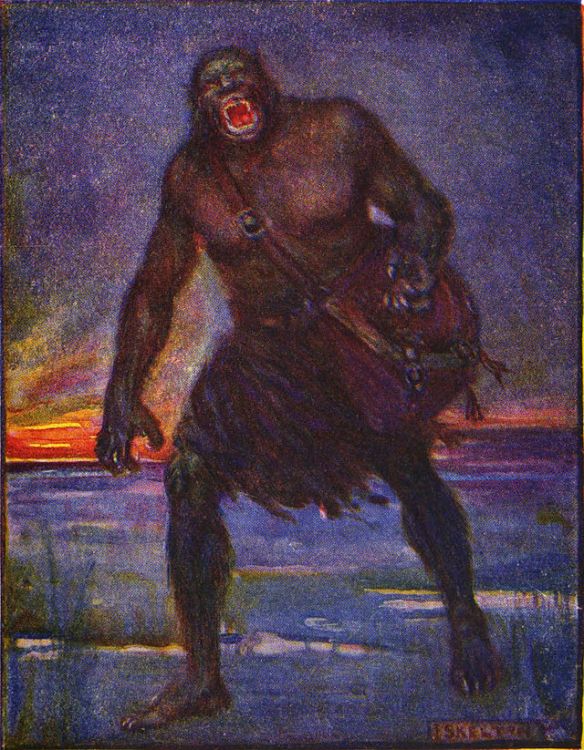

Grendel’s mother isn’t just some ghoul that comes around haunting halls, she’s a “water-wolf” (“grund-wyrgenne” (l.1518)), a “water witch” (“mere-wif” (l.1519)). So she’s still humanoid, but is, at least, given her titles (and maybe her nature in the eyes of an at times misogynistic culture), much more of an intellectual or spiritual threat than a physical one.

Sure, she grabbed Beowulf and dragged him down, but if you get into the spiritual element of the poem (read: the Christian element), it’s very easy to interpret Grendel’s mother dragging Beowulf down as tempting him. I mean, think about it, he’s this upright warrior for god who seems almost entirely chaste.

Plus, Beowulf’s beating Grendel shows that he’s nothing to be trifled with physically, and Beowulf is very pious about attributing his victory to god and fate. So where could the next big threat go except into the spiritual realm?

So it makes sense that the second threat Beowulf faces is more spiritual.

Who even knows how she “grasped” Beowulf when she was pulling him down? I’m imagining that she full on wrapped herself around him, almost like water itself.

The presence of water even adds a drowning motif, which, I’m not sure was commonly related to temptation at the time, but no doubt is now. Though, of course, there’s also the redemptive property of water in the rite of baptism, so, all’s not lost for Beowulf and his failed sword. A sword that, in Beowulf’s overly capable hands, just had to fail to increase his renown — otherwise, he’d just be another one who used Hrunting instead of the one man who used it to no effect.

How much of a threat do you think Grendel’s mother is to Beowulf? Is she more of a physical threat or a spiritual one?

Back To Top

How to Face a Water Witch

When fighting a “mere-wif”1 it’s important to be prepared.

Be sure to wear your best “fyrd-hrægl”2 for “hand-gemot”3. This will help you against the “mægen-ræs” that the “mere-wif”1 is bound to unleash upon you. In fact, if you’re particularly unlucky, she may show how feral she had to be to earn the epithet “grund-wyrgenne”4.

You’ll also want to bring along a “hilde-bille”5. It isn’t necessary to have a ” hring-mæl “6, nor is it recommended. These sorts of swords are fine against human opponents, but generally have no effect on your average “water witch”7. Any sword which can catch the light dramatically as you hold it aloft so that it can be your ” beado-leoma “8 while you sing your ” guð-leoð “9 will do. after all, the sword is mostly required to intimidate and parry the “mere-wif”1‘s attacks. Damaging such an opponent with any forged iron has long been thought impossible.

It is highly recommended that you do not fight a “mere-wif”1 on her own turf. Her familiarity with and power over water and the creatures of the deep is sure to prove overwhelming. And, if she brings you into a strange underwater cave, then may the Measurer, Lord of All, have mercy upon your soul. If you find yourself in such a situation, your wyrd is clear and inescapable.

1mere-wif: water witch. mere (sea, ocean, lake, pond, pond, cistern) + wif (woman, female, lady, wife) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

2fyrd-hrægl: corslet. fierd (national levy or army, military expedition, campaign) + hrægl (dress, clothing, vestment, cloth, sheet, armour, sail) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

3hand-gemot: battle. hand (hand, side (in defining position), power, control, possession, charge, agency, person regarded as holder or receiver of something) + (ge)mot (conflict, encounter) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

4mægen-ræs: mighty onslaught. mægen (bodily strength, might, main, force, power, vigour, valour, virtue, efficacy, efficiency, good deed, picked men of a nation, host, troop, army, miracle) + ræs (rush, leap, jump, running, onrush, storm, attack)

5grund-wyrgenne: water-wolf. grund (ground, bottom, foundation, abyss, hell, plain, country, land, earth, sea, water) + wyrg (wolf, accursed one, outlaw, felon, criminal) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

6 hilde-bille: sword. hilde (war, combat) + bill (bill, chopper, battle-axe, falchion, sword)

7 hring-mæl: sword with ring-like patterns. hring (ring, link of chain, fetter, festoon; anything circular, circle, circular group, border, horizon, rings of gold, corslet, circuit (of a year), cycle, course, orb, globe) + mæl (mark, sign, ornament, cross, crucifix, armour, harness, sword, measure) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

8beado-leoma: battle-light, sword. beadu (war, battle, fighting, strife) + leoma (ray of light, beam, radiance, gleam, glare, lightning) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

9guð-leoð: war-song. guð (combat, battle, war) + leoð (song, lay, poem) [A word exclusive to Beowulf]

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, Beowulf regroups and Grendel’s mother moves in.

You can find the next part of Beowulf here.

Back To Top