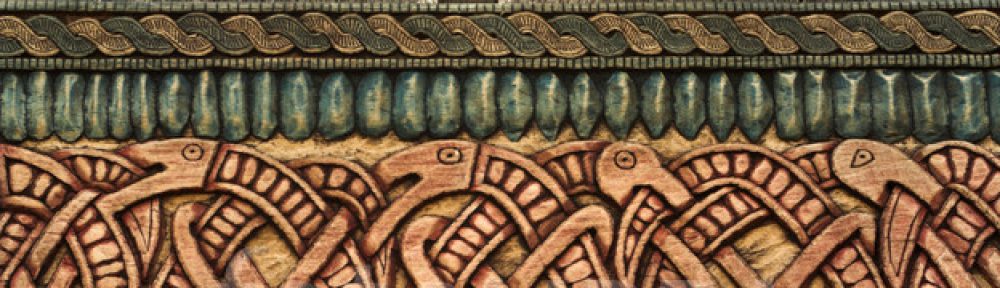

An illustration of Grendel by J.R. Skelton from Stories of Beowulf. Grendel is described as “Very terrible to look upon.” From: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stories_of_beowulf_grendel.jpg.

X

Then from him Hrothgar went among his warrior band,

the prince of the Scyldings left the hall.

The war chief would seek out Wealhtheow,

the queen consort. But the king of heaven had

against Grendel, as people later learned by inquiry,

set a hall guard; one with a special office to fulfill

for the lord of the Danes, a steadfast sentry against monsters.

Indeed that Geatish man eagerly trusted

the courage of his strength, the Measurer’s protection.

Then he did off with his iron corselet,

took the helm from his head, entrusted his ornamented sword,

servant of the best iron, to his men

and he commanded them to keep his war gear.

Spoke he then some good boast words,

Beowulf the Geat, before he laid himself down:

“I consider my own prowess with battle work unbowed

when compared to Grendel;

as Grendel himself slays without sword,

that thief of life, I shall do the same.

He has not the advantage, that he shall slay me,

though he hew away my shield, though he be vigorous in his

evil deed: but we this night should

forego the sword, if he seeks to dare

a battle beyond weapons, and afterwards wise God

shall decide which of us, oh holy Lord,

is worthy of glory, as He deems proper.”

He kept himself bold then, took pillow

to cheek with his band, and he among the many

ready seafarers gave themselves over to hall-rest.

But none of those thought that they should afterward

ever see their dear land again,

their people or their towns, return to where they had been raised.

They all envisioned, through sleep-smeared eyes, those stories

of how things had been in that wine hall, how death had come

for many of those Danish people. But to that hall-guard the Lord gave

woven success in war, the Danes would thank the Weder people,

both would find joy and help, that they the fiend there

would fully overcome through that one’s strength,

by his own might. The truth is shown,

that mighty God rules humankind

always. In the deepest night

came slinking the wanderer in shadow. The warriors slept,

when they should have been holding that hall.

All but one. It was known of many people,

that they might not, as long as the Measurer allowed it not,

be brought to the shadow beneath by the sin-stained,

but that one woke with wrath in enmity

pledged enraged battle to the creeping creature.

XI

Then Grendel came from the moor under misty cliff

bounding. He bore god’s ire,

meant that sinner against humankind

to ensnare some in that humbled hall.

Raging beneath the heavens, he headed to Heorot,

the gold hall best known to men,

shimmering with ornaments. That was not the first time

that he the home of Hrothgar sought out.

But, never had he in earlier days nor afterwards

found a thane so hard in the hall.

When he came to the hall,

the joy of journeying men to rob, the door’s

secure fire-forged bar soon gave way, as he touched it:

it burst open for the one meditating on mischief. Standing at the hall’s mouth,

his own twisted into a raging smile. Quickly then

that fiend on the shining floor trod,

went with hatred at heart; he stood, in his eyes

an unfair light like flame.

Saw he in the hall many men,

a sleeping peaceful host gathered all together,

a heap of youths. Then his heart roared anew.

He intended to sever, before the day returned,

the terrible fierce assailant, from each one of those sleepers

their limb and life, expected he a lavish feast

to come about. Yet such was not set as fate,

that he would be allowed more of mankind

to taste during that night. The mighty looked on,

kin of Hygelac, to see how the enemy

with his calamitous grip would fare.

That fierce foe gave no thought to yielding,

but he swiftly seized at his first chance

a sleeping warrior, slit through him heedlessly,

bit through bone-locks, drank blood from the veins,

swallowed sinful morsels; soon he had

consumed all of that one,

feet and hands. Forward and nearer he stepped,

his hand grazed against the strong-hearted

warrior at rest — the fiend’s fingers reached

for him. He, the Beowulf, hastily took the arm

and sat up to strengthen his hold.

Soon that master of the wicked deed found one

like none he had ever met in all the earth,

no other in any region of the world

had so great a hand grip. At heart Grendel grew

panicked, feared he might never break free.

In his mind Grendel was eager to escape, wished he could flee to his darkness,

seek and join his devil kin. He could feel that further life for him was not there,

only one like none other he had ever encountered in all his days.

The goodly kin of Hygelac was mindful then

of his evening boast, he stood sternly upright

and secured his grip. His fingers were bursting,

the beast was squirming to escape. The man stepped toward the monster.

That creature intended, whenever he might do so,

to flee to the fen-hollow. Grendel could feel his fingers

loosening under the foe’s grip, it was indeed a terrible journey

that the horrible fiend took to Heorot that night!

The noble hall resounded, all of the Danes,

citizens, each violently stirred,

all awake in broken ale-dream distress. Both within were warring,

fierce were the hall wardens. That room resounded;

it was a great wonder, that the wine hall

held out against those boldly brawling,

that fair house; but it was yet secure

inward and outward in its iron bonds,

skilfully smithed. In there from the floor

were wrenched mead benches many, as I have heard,

each gold adorned, where the hostile ones fought.

Never before thought the wise of the Scyldings

that any man or means ever could be found

to bring the grand and antlered hall down,

destroy it by cunning, unless in the hottest embrace

it was swallowed by flame. Sounds newly rose up

often, horrible fear came over over

the Danes, each and every one of them

heard wailing while outside Heorot’s walls,

a chant of terror uttered by god’s adversary,

it sang of defeat, a wound to sear and sever

the captive of hell. He held him tight,

that man was the greatest in might

all the days of this life.

XII

For nothing at all would Beowulf

allow the death-bringer to leave alive,

he did not consider that one’s days of life of

any worth to anyone anywhere. Then the mobile host

moved swiftly to defend Beowulf with their fathers’ swords,

they wished to defend the very soul of their leader,

those of the famed people, where they might do so.

But they knew not that their work was in vain,

the tough-spirited war-men,

that each man’s looking to hew the beast in half was faulty,

their seeking his soul with the sword point unsuccessful: that sin-laden wretch,

by even the best iron in or on the earth,

by any battle bill, could not at all be touched,

for he had forsworn the use of any weapon of war,

each and every edge. Yet his share of eternity

in the days of this life

would be agonizing, and the alien spirit

into the grasp of fiends would journey far.

Then the one who in earlier days had

completely changed the heartfelt mirth of man

for transgression — the one who sinned against god —

realized that his body would not endure,

for the spirited kin of Hygelac

had him firm in hand; as long as each of those fighters was living

he was hateful to the other. What a wound

endured the terrible creature: his shoulder split

into an open and immense red mouth, sinews sprung loose,

bone joints split. Beowulf was given

war glory; whereas Grendel would thence

flee with his mortal wound to the fen cliffs

seeking out a joyless home. He knew for certain,

that his life was coming to an end,

his days were now numbered. Every one of the Danes’

wishes were fulfilled after that deadly onslaught.

That place had been cleansed, after that one from afar arrived,

clever and brash, at the hall of Hrothgar,

rescued it from strife. Gladdened by his night work,

fodder for the flame of fame for courage, that man of Geatish

folk had fulfilled his boast to the Danes,

had cured a great wound,

parasitical sorrow, that had earlier been a daily part

of the misery they were to suffer —

no little grief. It was an open token,

when the war-fierce one placed the hand,

arm and shoulder — there all together was

Grendel’s grip — under the broad roof.

XIII

It was that morning, as I have heard,

when to that gift-hall came many warriors;

chieftains marching from regions ranging

far and near to see that wonder,

the remnants of the resented one. None of those there

thought upon that one’s death sorely,

where the trail of the fame-less transgressor showed

how he went with weary-heart on his way,

the evil that was overcome, to the water-sprites of some pond,

the fated and fugitive leaving a trail of lifeblood.

There they guessed the water swelled with blood,

there repulsive waves surged, all mingling,

hot with gore, sword-blood tossing;

there the fated to die hid, when he, joy-less,

in fen refuge laid aside his life,

his heathen soul. From there hell took him.

Afterwards the old war-wagers went out,

so too did many youths go on that merry journey,

from the sea high-spirited horses they rode,

warriors on their steeds. There was Beowulf’s

glory retold; many oft spoke of it,

that in neither north nor south between the two seas

was there any other such man on all the face of the earth,

and under the sky’s expanse was there no better

shield bearer, one worthy of kingship.

Though they indeed found no blame with their lord and friend,

gracious Hrothgar, for he was a good king.

Meanwhile the battle-reputed let the horses trot,

in contests the bay horses sped,

there they found the path quite fair,

they thought it best. Around one of the king’s thanes

was a man made of stories, mindful of many tales,

such that he was in old tradition

immersed, bound words one to the other

according to appropriate meter. The man began again

of Beowulf’s struggle to smartly sing

and quickly made a new narrative account,

wrangled words. Of everything he spoke,

what he of Sigemund had heard said,

deeds of courage, many not widely known.

He spoke of the wrangling of Wælsing’s son, Sigemund’s wide wanderings

where that warrior’s child was not often recognized

nor the feud and wicked deed known but to Fitela, the one with him.

For Sigemund would tell Fitela of such things,

from uncle to nephew, as they were always

companions bound by need come every strife;

they had a great many of the giants race

slain with their swords. Sigemund’s fame saw

no small surge after his death day,

after he had in cruel combat killed the dragon,

the hoard’s guardian. Under the grey stone,

the nobleman’s son, alone he dared to do

the dangerous deed; Fitela was not with him then.

Without that comrade he plunged his sword through

the wondrous wyrm, so that it stuck in the wall,

that lordly iron. The dragon died its death.

His courage over the foe won him its treasure fully,

so that he ring hoards had to give

as he saw fit; a boat they loaded,

they bore in the ship’s bosom bright treasures,

Waels’ son; the hot wyrm melted.

[]His fame was pushed most widely

among the nations, protector of warriors,

for deeds of courage — he prospered from then after —

after Heremod retired from war,

his strength and courage. He had his power stolen

when ambushed by the enemy Jutes and his forces

were quickly slain. His sorrow oppressed him

far too long; to his people he waned,

to all his nobles his life grew too full of care.

That campaign was often a source of anxiety for

many wise men before the time of king Heremod’s brash way of life,

it made those miserable who relied on him for relief,

those that wished that every prince would prosper,

receive his patrimony, protect the people,

their stores and their strongholds, be a man of might,

uphold the ancestral home of the Scyldings. Just the same there,

Beowulf, the kin of Hygelac, to all humankind

became a decorated friend. Yet sin still slinked in.

The contending continued among

the tawny mares racing on the sand. By then the morning light

shoved and rushed over the horizon. There came many retainers,

all bold-minded, to that high hall,

to see that strange object; the king himself

from the bed chamber, guardian of the ring-hoard,

walked with a sense of leading an army,

of renowned virtue, and his queen with him

tread the path to the mead hall with her maiden troop.

—

Want more Beowulf? Continue the poem here!