Synopsis

Translation

Recordings

A Grisly Joke

A Monstrous Listing

Closing

Back To Top

Synopsis

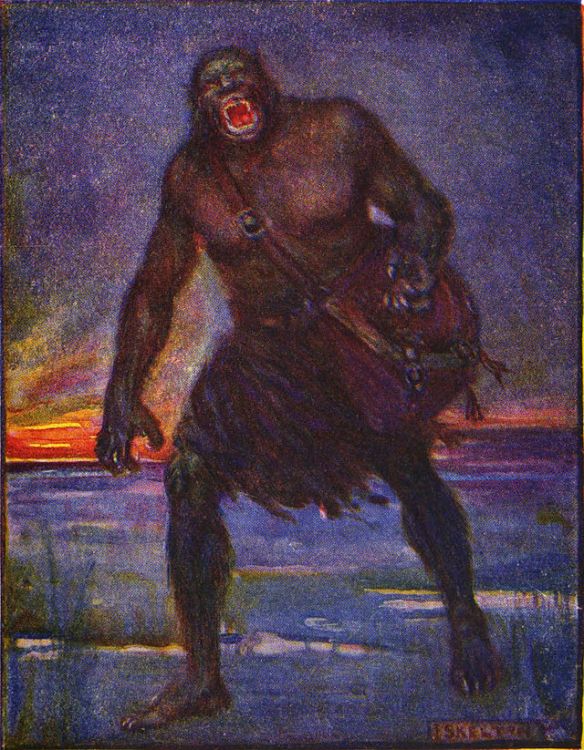

Hrothgar and his wisest thanes see a grisly sight at the Grendels’ doorstep.

Back To Top

Translation

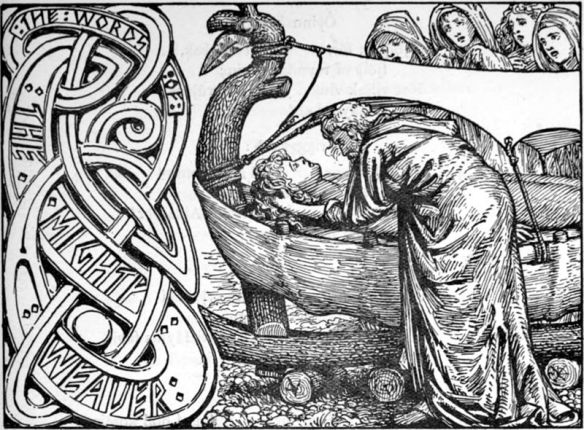

“The prince’s thanes then rode on

over steep rocky slopes, around narrowly winding paths,

through ways that fit just single file soldiers, up trails unknown,

precipitous headlands, lined with homes of water monsters.

He went on ahead with a handful of the wise,

to see that strange place; they looked about

until suddenly they found a patch of mountain trees

all growing out over grey stones,

a joy-less forest; waters stood beneath them,

blood-stained and turbid. To all the Danes gathered there,

friends of the Scyldings, the sight caused harsh suffering

at heart, bringing the same heaviness to each of the many thanes,

striking each of them with grief, once they found

the head of Æschere on the cliff by the water’s side.”

(Beowulf ll.1408-1421)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

A Grisly Joke

Hrothgar’s ride up to the mere is quite vivid — in a King James Version of the Bible sort of way.

The first few lines of this passage (and the last few of last week’s) are sparse in their description. And yet, somehow these lines say a lot in their handful of words. It certainly sounds like the mere is incredibly isolated, almost as if the journey there (though it’s “not many miles” away (“Nis þæt feor heonon/milgemearces” (l.1361-1362)), as Hrothgar’s said earlier in the poem) has taken them to an entirely new world. A world of crooked trees growing over stony ground that’s also swampy and saturated with ever-churning waters. It does indeed sound like a grim place. But topping it all off is the discovery of Æschere’s head.

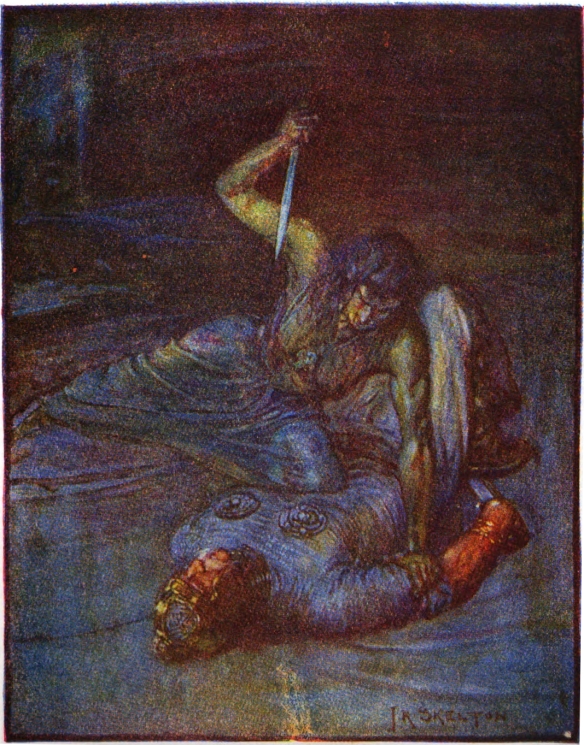

As we’ll find out once the poem gets to Beowulf’s pursuing Grendel’s mother, the Grendels’ home is in this water. And so, since this cliff is at the water’s side, I can’t help but think that it is the Grendels’ equivalent of Heorot’s gables.

After Beowulf defeated Grendel he hoisted his opponent’s arm up into those gables as a prize and a sign of triumph. Of course, taking that trophy was fatal for our 12-year terror, Grendel. Likewise, taking off Æschere’s head would have been fatal for him. Also likewise, his head is being similarly displayed as a trophy and as a sign of triumph in the feud.

But now, since it’s Æschere’s head and not the limb of some miscellaneous monster, we’re meant to feel just as sad at heart as the Danes who look upon the grim sight with Hrothgar. And it’s easy to feel it. I mean, from the time that Grendel’s mother takes him it’s pretty clear that Æschere is dead. But even so, seeing such grisly proof that he is indeed gone is still pretty devastating.

And yet, the parallel to Grendel’s arm makes me wonder what the poet was trying to say here.

Maybe the poet’s driving home what I’ve pointed out before, that Grendel and Grendel’s mother, for all of their monstrousness, are still beings with reason and with a capacity for empathy and a strong sense of family. A sense strong enough to inspire Grendel’s mother to barge in on a hall full of armed warriors with nothing but the fear of her they feel for protection.

Maybe giving such a quality to monsters was meant to show how much the idea of family, an often elevated and ennobled feeling, is really just an animalistic instinct. And that the preyed upon and the hated feel it just as much as those who are in an elevated position of privilege.

Maybe the poet is exercising some dark humour. Æschere’s head being on display is a little elbow in the ribs, a little flip of the bird from monster kind.

What do you make of this scene? Is it just a grisly display of how low the Grendels will go or is it a little wink from the poet in some way?

Back To Top

A Monstrous Listing

Speaking of Old English humour, I think you could probably find a joke real estate listing like this if real estate listings were a thing in the days of Beowulf and Hrothgar:

Make your way along the “an-pað”1, up the “stan-hlið”2, and you’ll find a terrible “nicor-husa”3. This “nicor-husa” comes complete with a “wyn-leas”4 “fyrgen-beam”5 out front and an abysmal “holm-clif”6 view. Starting at three severed thanes’ heads or best offer.

Or, in Modern English:

Make your way along the narrow path, up the rocky slope and you’ll find a terrible sea-monster’s dwelling. This sea-monster’s dwelling comes with a joyless mountain-tree out front and an abysmal sea-cliff view. Starting at three severed thanes’ heads or best offer.

1an-pað: narrow path. an (one, each, every one, all) + pað (path, track)

2stan-hlið: rocky slope, cliff, rock. stan (stone, rock, gem, calculus, milestone) + hlið (cliff, precipice, slope, hill-side, hill)

3nicor-husa: sea monster’s dwelling. nicor (water-sprite, sea-monster, hippopotamus, walrus) + husa (house, temple, tabernacle, dwelling-place, inn, household, race)

4wyn-leas: joyless. wyn (friend, protector, lord, retainer) + leas (without, free from, devoid of, bereft of, false, faithless, untruthful, deceitful, lax, vain, worthless, falsehood, lying, untruth, mistake)

5fyrgen-beam: mountain tree. fyrgen (mountain) + beam (tree, beam, rafter, piece of wood, cross, gallows, ship, column, pillar, sunbeam, metal girder)

6holm-clif: sea-cliff, rocky shore. holm (wave, sea, ocean, water) + clif (cliff, rock, promontory, steep slope)

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, everyone in the party is entranced by the beasts in the water.

You can find the next part of Beowulf here.